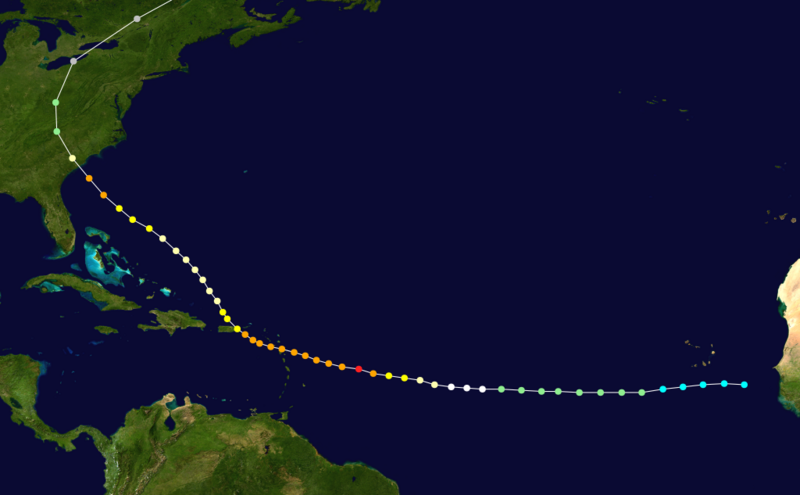

Hugo as a Category 5 (classic buzzsaw shape!)

Moderator: S2k Moderators

Derek Ortt wrote:the first NOAA flight tried to penetrate Hugo at 1500 feet. Dvorak estimates had it as a category 3 hurricane.

Ended up losing an engine and the AF had to direct the NOAA plane out of the storm

friends.

friends.

HurricaneBill wrote:Derek Ortt wrote:the first NOAA flight tried to penetrate Hugo at 1500 feet. Dvorak estimates had it as a category 3 hurricane.

Ended up losing an engine and the AF had to direct the NOAA plane out of the storm

I think I read somewhere that after that, recon was no longer allowed to penetrate a storm at very low altitudes.

Also, wasn't penetrating at a low altitude what caused the plane to crash during Hurricane Janet in 1955?

Derek Ortt wrote:the rainbands were flown much lower during Isabel

How Hurricane Hugo changed South Carolina forever

By DAVID LAUDERDALE

dlauderdale@islandpacket.com

843-706-8115

Published Saturday, September 19, 2009

Hurricane Hugo was a killer.

We knew that as we hunched over tables in the composing room at The Beaufort Gazette, our X-Acto knives slicing in breathless facts about a storm headed straight at us.

It was a Thursday afternoon 20 years ago this week. We were urgently trying to make an early press run for a newspaper no one would be there to deliver, and few would ever read. Every indication was that before the next day dawned, there would be no homes left to deliver them to anyway.

At 4 p.m., the chief national meteorologist in Charleston told us: "It has strengthened considerably.

"It's hard to tell where there will be a dead strike ... but with hurricane-force winds extending out 100 miles and tropical storm winds extending out 250 miles from the center, it's not finished yet with us."

Nothing more accurate has ever been printed in this newspaper.

As we slugged through the afternoon of Sept. 21, 1989 -- Beaufort and Hilton Head Island by then eerily empty -- Hurricane Hugo ticked a degree or two to the north.

Our press ran at about 6 p.m. -- just 12 hours after a mandatory evacuation was ordered for Beaufort County, firefighters banging on doors begging everyone to flee.

At midnight, Hurricane Hugo blasted ashore near Charleston, and South Carolina would never be the same.

'It's gone'

Early the next morning, we knew we were clear to go home. We found National Guard troops patrolling an empty Hilton Head. Palmetto Electric would soon flip the switch to restore power, and we'd grouse about all the debris shaken from the trees.

And then it hit us. We started pulling Associated Press photographs off a creaky machine that moaned like every photo it slowly spit out would be its last.

Those black-and-white images remain flash-frozen in my mind. We saw a sailboat perched on a Charleston street. We saw boats-- shrimpers, yachts and sailboats -- piled on top of each other in a marsh like toys in a baby's tub. We saw power poles tossed like Tinkertoys. The swing span of the Ben Sawyer Bridge to Sullivan's Island and the Isle of Palms lurched dead into the water.

We saw acres of pine trees snapped off at 15 feet by winds well above 100 mph, or perhaps one of the 3,000 tornadoes Gov. Carroll Campbell told us ripped along in Hugo's roaring train of misery.

Then we got a phone call from our sister paper in Rock Hill, near Charlotte. Before we could say, "Thanks for your concern, but we're OK," we heard that Hugo hit them, not us. It knocked out power and downed so many trees four hours away, it would take years to remove them all.

Many Lowcountry evacuees had inadvertently escaped into the path of a hurricane that killed about 50 people -- 13 of them in South Carolinia -- and caused $10 billion in damage from the Caribbean through the United States.

That afternoon, we saw raw footage from a state helicopter that buzzed a battered coastline from Ocean Drive to Daufuskie. Pawleys Island was split in two. Pilings stood in the ocean where a large restaurant used to be. Sand covered roads. We could see the mess in the bedrooms of house after house with no roof. In places there was nothing at all where rows of houses used to be.

"You go down these beaches and there is no beach," the governor said. "It's gone."

Call it love

Hurricane Hugo showed us the power that nature has over mankind and our grandest little designs. We stand by the mighty sea as if we're shaking our fist at the Almighty. We get knocked down. We wait in sweltering lines begging for ice like paupers. And we rush back like ants to rebuild.

Nothing I've ever seen compares to what took place here after the storm. The outpouring of help -- love, if you will -- from this community to our fellow man up the coast and inland throughout the Carolinas was quick, relentless and long-lasting.

Overnight, our worries changed. We went from fretting that the dedication of the new football stadium at Hilton Head Island High had been postponed, to rebuilding full communities.

Our churches adopted other churches, and sometimes whole towns. Scores of volunteers met every morning to caravan into the wasteland up the coast where old ladies sat in debris and said, "I'm tired. I'm so tired."

Our newspaper chronicled massive comings, goings and giving. We inserted a grocery bag in the paper, with a list of specific items people in Sumter County needed. Our readers responded with truckloads of full bags. That was minuscule in the avalanche of compassion.

A local radio station with a signal reaching into the Charleston area quickly dropped everything to broadcast the needs and coordinate responses. It started almost by accident, and mushroomed. Volunteers flooded the station, the whole thing got computerized, and it went on for months.

Oprah Winfrey, who had recently gone national, came to Charleston to see our people for herself and show us to the nation. She raised $1 million for the Lowcountry.

The Rolling Stones and many others helped. But most of the news was far less glitzy. It was of mud, poverty, long lines, lost careers, red tape, con artists, desperation and new beginnings.

Meanwhile, the federal response disappointed. U.S. Sen. Fritz Hollings of Charleston told his colleagues in Washington that the Federal Emergency Management Agency was "... the sorriest bunch of bureaucratic jackasses I've ever known."

Change

Looking back on it, it's jarring how crazy we were.

H.E. McCracken Middle School in Bluffton was filled with more than 400 evacuees. Battery Creek High was so full some who sought shelter there were sent to Mossy Oaks Elementary School.

Some of our shelters were within spitting distance of water. And they were to keep people safe in the face of a Category 4 hurricane with storm surges approaching 20 feet.

We could easily have experienced one of the most horrifying stories to come from Hurricane Hugo. It happened at Lincoln High School in McClellanville, a beautiful little fishing village between Charleston and Georgetown that was all but destroyed. About 70 people were in the band room, riding out the storm. During the night, water first creeped under the door then flooded the room. It crested within a couple of feet of the ceiling. Parents roped children to their bodies in the pitch black. An 82-year-old lady was held aloft. They all survived.

Today, that scene would never happen.

And as the coastal population has generally doubled over the past two decades, the idea of ordering an evacuation of Beaufort County 18 hours before a hurricane makes landfall is bone-chilling.

Most people left voluntarily the day before, but today evacuations require much more time.

And today we have tighter building standards.

Hurricane Hugo also taught us the value of leadership. Gov. Campbell and Charleston Mayor Joe Riley were champions.

It taught us the vulnerability of man, the kindness of man and the resilience of man.

Here at the newspaper, we still hunker down when normal people get out of harm's way.

But we never -- ever -- underestimate the killing power of a hurricane.

Email Article | Print Article | Feeds | | Search the Archive

Users browsing this forum: ljmac75 and 89 guests